Human evolution is one long crime scene with half the evidence missing and the main suspects already dead. We know the rough story: small, ape-like creatures in Africa, and somehow, over millions of years, people like you and me, sitting here thinking about this. But the weird part is how many key steps in that story are still not clear at all.

I want to walk you through five of the biggest gaps, but in plain language, like we’re sitting at a table with a pile of fossil bones between us, trying to make sense of them. As we go, I’ll keep asking you questions, because the truth is, your own everyday life is a clue to these puzzles.

Let’s start with your legs.

You walk on two feet all day without thinking about it. You stand in lines, climb stairs, run for the bus. But for most of primate history, walking on two legs all the time was not normal. Our early relatives were more like today’s chimps: good at climbing, comfortable in trees, flexible in how they moved.

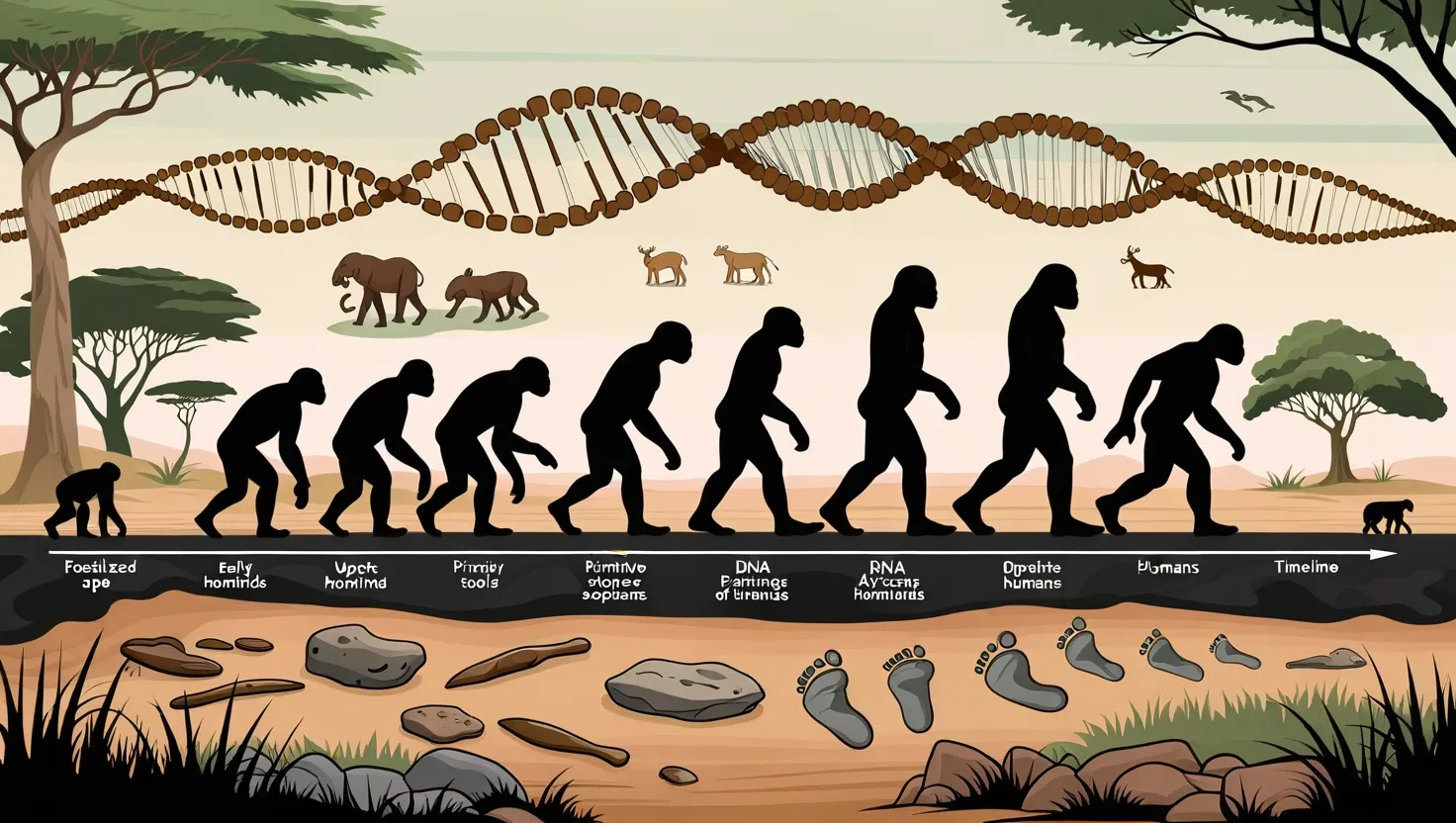

Then, more than 4 million years ago, something strange shows up in the fossil record: hips, knees, and feet slowly changing for full-time upright walking. Toes lining up. Pelvis reshaping. The spine curving like an S. We even have ancient footprints pressed into volcanic ash that show someone walking much like us.

The confusing part is not whether this happened. It did. The question is why. Why would an ape that already climbs well give up that advantage and fully commit to walking like we do?

You’ve probably heard simple answers: to see over tall grass, to free the hands for tools, to carry babies or food, to stay cooler in the hot sun. These all sound tidy, but every one of them has problems.

Think about it. If seeing over grass was that helpful, why don’t other animals stand up all the time? A gazelle has great vision but doesn’t try to walk on two legs. If freeing the hands for tools was the key, why did upright walking appear before we see clear evidence of complex tools? And if it was about staying cooler, why didn’t other African mammals evolve the same trick?

Here’s an odd detail many people miss: early upright walkers still had long arms and curved fingers, good for climbing. Their bodies look like a mix: part tree-climber, part ground-walker. So the shift was not a sudden “we now walk like humans.” It may have started as part-time behavior, like spending some time in trees and some time walking between them.

Let me ask you something: if you had to walk 10 kilometers every day in burning heat, carrying food or a child, which matters more to you—speed or energy saving?

Many scientists think upright walking, once the body adjusted to it, was just more energy-efficient for long distances than moving on all fours. Less energy per step means you can travel farther to find food, water, or safe sleeping spots. That quiet, boring advantage over millions of years might beat all the flashier explanations.

But here is the twist I find most interesting: bipedal walking may not have started on open grasslands at all. Some fossils suggest our early ancestors walked upright even in mosaic environments with trees and mixed terrain, not endless plains. That means walking on two legs might have started as a flexible way of moving through varied landscapes, not just as a grassland trick.

So the first mystery is simple to say but hard to answer: did we stand up to adapt to new landscapes, to save energy, to carry, to keep cool, to show off, or some mix of all this over long stretches of time? There may never have been a single reason, just lots of small pressures pushing in the same direction.

“Not only is the universe stranger than we think, it is stranger than we can think.” — Werner Heisenberg

Sometimes I feel the same way about our own skeletons.

Now, look at your head. Put your hand on your forehead. That big round skull is the second mystery.

Our brains are huge for our body size. This sounds flattering, but from a biology point of view it’s a headache. Big brains use a lot of energy. Your brain is a small percent of your body weight but eats around a fifth of your daily energy. For an animal living with no fridges, no supermarkets, and no delivery apps, that is a serious bill to pay.

So why did natural selection allow that bill to grow?

Over the past two million years, especially with species like Homo erectus and then later Homo sapiens, brain size ballooned quickly by evolutionary standards. Yet for a long time, stone tools stayed pretty simple, and life was still harsh. It wasn’t an instant “big brain, big genius” story.

Here is something many people don’t realize: a bigger brain is not automatically better at everything. It is also slower to develop. Human children are “helpless” for years compared with other mammals. That means parents and other group members must invest time and care. So somehow, a social system had to evolve that could support many slow-growing, energy-hungry children.

Do you see the loop here? For big brains to work, you need more cooperation. But to manage complex cooperation, you may need more brain power. Which came first?

Some researchers argue that social life itself drove brain growth. Living in groups means keeping track of relationships, alliances, cheating, fairness, reputation. Think of your own daily life: family drama, office politics, friendships, social media. It’s not just survival; it is constant mental chess. Our ancestors may have been under similar pressure. Those who could read others better, plan ahead, smooth conflicts, and coordinate hunts might have had more children.

Others point to food. Cooking, for example, makes calories easier to get from tough or raw foods. A brain that can invent, share, and protect new ways of getting food earns extra energy, which then supports an even bigger brain. This is like a positive feedback loop: smarter brains find better food strategies, which feed even smarter brains.

Have you ever thought about how weird it is that we can imagine things that don’t exist, like dragons or imaginary futures, and then build real plans around pure ideas?

That leads straight into the third mystery: language.

We talk so easily that we forget how strange speech really is. I move air through my throat. Tiny muscles shape sounds. Your ears pick up vibrations. Your brain then turns them into meaning. In seconds, I can move ideas from my mind into yours, without either of us seeing the thing we’re talking about.

Now here is the hard part for scientists: language does not fossilize. Skeletons, tools, hearths, yes. Conversations, no.

We can guess from brain areas, from the shape of the throat, from genetic hints, from the complexity of tools and art, but we do not have a clear “this is the first sentence ever spoken” moment. Some researchers think fully modern language appeared fairly late, maybe within the last few hundred thousand years. Others think that simpler proto-language may go back much further.

Ask yourself: how far can you get in life with no words at all?

You can still point, gesture, show, make faces, and use tone. Apes, dogs, even birds do some of this. So language likely did not appear from nothing. It probably grew step by step from more basic communication: calls, gestures, shared attention to the same object, teaching by demonstration.

The real puzzle is not sounds. Even birds can copy complex patterns. The hard bit is structure: grammar. When you say “the dog chased the cat,” you know who did what to whom, even if you never studied grammar rules. Your brain handles subject, verb, object automatically.

At some point, human minds gained the ability to build endless new sentences from a limited set of words. That is like having a small box of Lego bricks but building infinite new shapes. When did that mental ability appear, and what exactly changed in the brain to allow it? We don’t know.

Here is a famous line that applies well to language and science itself:

“The important thing is not to stop questioning.” — Albert Einstein

We still do not know whether Neanderthals, for example, had language as rich as ours. They had similar brain sizes, used tools, likely cared for their sick, and probably told some kind of stories. But how close were their conversations to ours? Did they gossip? Did they argue abstract ideas? The fossils are silent.

Speaking of Neanderthals, let’s talk about the “ghosts” in your DNA.

Many of us carry small bits of Neanderthal or Denisovan genes in our genomes. That means our ancestors did not just wave at these other human groups from a distance. They met, lived together, and had children.

For a long time, people pictured a simple ladder: from some early ape-like ancestor to Homo erectus to Neanderthals to us. Now we know it was more like a tangled bush. Different human species overlapped in time and space, mixing and replacing each other in various ways.

But big questions stay stuck. When our ancestors met Neanderthals, what was it like? Was it mostly violent competition, or did they share ideas and partner up in more peaceful ways? Were there trade networks? Did they learn new hunting or tool-making tricks from each other?

Think about this: if you suddenly met another group of humans who looked a bit different but could clearly make tools and fires and cared for their young, what would you assume? That they are “animals”? Or that they are some strange version of “us”?

There is another question that digs deeper: why are we the only human species left?

Neanderthals survived harsh ice-age conditions for hundreds of thousands of years. They were tough, skilled, and adapted to cold climates. Denisovans left traces in people living today in parts of Asia and Oceania, suggesting they, too, were well adapted to their regions. Yet in the end, only Homo sapiens survived everywhere.

Some ideas: maybe we had slightly more flexible social networks, allowing larger groups to share resources and information. Maybe we specialized in long-distance trade, connecting far regions. Maybe our language allowed faster spread of innovations. Maybe diseases spread when groups met, and some lineages were wiped out more than others.

None of these ideas fully solves the puzzle. The reality may be a mix of climate shifts, competition, cooperation, random events, and small mental and social advantages adding up over time.

Here is a simple but powerful thought to hold onto:

“We are just an advanced breed of monkeys on a minor planet of a very average star.” — Stephen Hawking

We often forget that other humans once shared this planet with us, with their own histories and, likely, their own myths about the world.

Now we come to the last mystery: the sudden burst of art and complex culture.

If you look at the archaeological record, for a long time tools change very slowly. Basic stone flakes, then slightly better shapes, but not much decoration. Then, in what feels like a short window in evolutionary terms, we see things like beads, carvings, cave paintings, musical instruments, and very finely worked tools. It’s as if someone flipped a “creativity switch.”

Of course, it was not a real switch; it still took thousands of years. But compared with the earlier millions, it looks fast.

Why then? Why not much earlier, or much later?

Some people think there was a genetic change that suddenly boosted our capacity for symbolic thinking—the ability to let one thing stand for another, like a painted animal standing for a story, or a carved mark standing for a clan. Others argue that the brain was already capable, but social conditions were not right until groups became dense enough and stable enough to support full-time artists, teachers, and innovators.

Let me ask you: if you were living on the edge of survival every single day, would you spend precious time and energy painting a bison on a cave wall?

You might, if that painting had social or spiritual weight. Maybe it helped teach hunting routes. Maybe it bound the group together through shared rituals. Maybe it signaled identity: “we are this group, not that one.” Or maybe it expressed hope and fear in a world full of danger.

The “suddenness” of art might also be an illusion. Perishable art—on wood, skin, or in the sand—rarely survives. We only see what stone, bone, and cave walls can keep for us. So our picture may be skewed toward rare, durable forms of expression.

Still, something clearly changed in how our ancestors thought about themselves and their world. They did not just survive; they started to represent, imagine, decorate, and tell shared stories. At that point, biology and culture started to feed into each other in powerful ways. Cultural habits spread and stuck, even when genes stayed the same.

Here is a line that captures this shift from simple survival to reflective thought:

“The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and true science.” — Albert Einstein

Art, religion, science, law, money, nations—all of these are, in a sense, shared stories. Our ability to believe in things that exist only because we collectively agree on them might be the most “human” thing about us. Yet we still do not know exactly when and how that ability crossed the threshold from “animal clever” to “human symbolic.”

So where does this leave us?

We have five huge gaps: why we stood up, why our brains grew so big, how language truly began, how we related to other human species, and what set off the rush of art and complex culture. Each mystery is tied to how you live right now.

You walk on two legs. You carry an expensive brain in your skull. You speak in sentences. Your DNA carries traces of old meetings with now-vanished cousins. You live in a world thick with symbols, tools, art, and shared stories. Your ordinary day is built on extraordinary ancient decisions that no one consciously made.

Let me end with a question only you can answer for yourself: when you think about these gaps in our story, do they make you feel small or special?

For me, they do something simpler: they make me curious. They remind me that it is okay not to know, as long as we keep asking better questions.

As one physicist put it:

“I don’t feel frightened not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without any purpose, which is the way it really is as far as I can tell.” — Richard Feynman

Human evolution is not a finished book. It is more like a partly burned library: some shelves intact, some pages missing, some words smudged, some chapters never written down at all. Our job is not to pretend we have the full story. Our job is to look honestly at the gaps, use every tool we have—from fossils to genes to careful reasoning—and then admit where the mystery still stands.

And as you walk, talk, think, and create today, you carry those mysteries in your own body and mind.