The Hubble Tension: When the Universe’s Expansion Doesn’t Add Up

Imagine you’re trying to measure how fast a car is moving. One method involves tracking its position over time. Another involves analyzing the sound of its engine. Both methods should give you the same answer, right? But what if they don’t? What if one says the car is going 70 miles per hour while the other insists it’s going 76? That’s essentially what’s happening in cosmology right now, and it’s creating what scientists are calling a genuine crisis.

Our universe is expanding. We’ve known this since Edwin Hubble made his groundbreaking observation nearly a century ago, and it fundamentally changed how we understand reality. But here’s the troubling part: when we measure how fast this expansion is happening, we get two completely different answers depending on which method we use. This contradiction, known as the Hubble Tension, is one of the most pressing puzzles in modern physics, and it’s forcing us to question whether we actually understand the cosmos as well as we thought we did.

The expansion of the universe is measured using something called the Hubble Constant. Think of it this way—imagine the universe as a giant balloon covered with dots representing galaxies. As you blow air into the balloon, all the dots move away from each other. The Hubble Constant tells us how fast these galaxies are moving apart. Scientists express this speed in kilometers per second per megaparsec, which is a fancy way of saying how many kilometers galaxies move apart for every unit of cosmic distance we’re measuring.

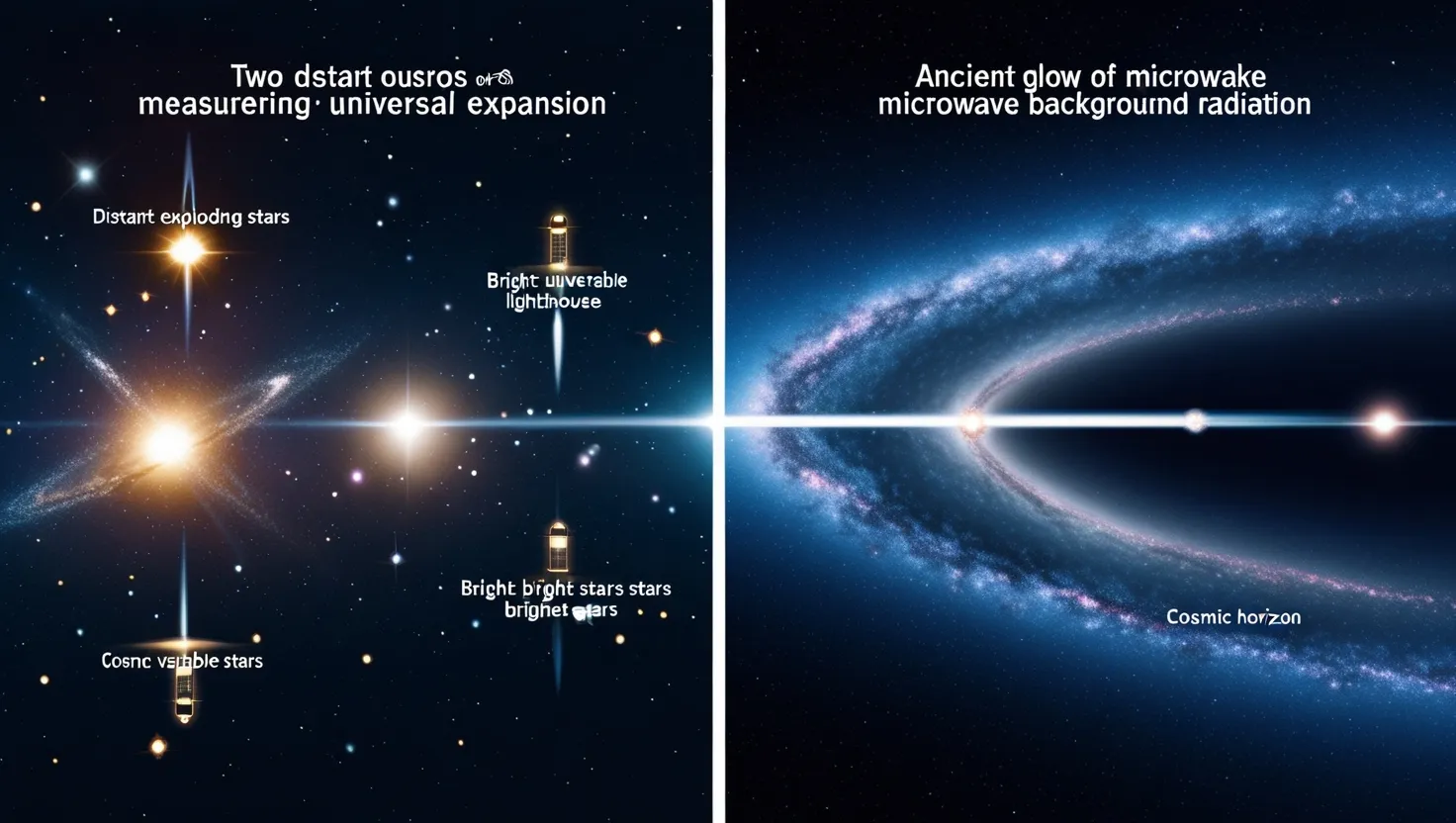

Here’s where things get interesting. The first method of measuring this expansion rate uses what astronomers call “standard candles.” These are objects in space that we know the true brightness of—specifically, certain types of exploding stars called Type Ia supernovae and stars called Cepheid variables. By comparing how bright they actually are with how bright they appear to us on Earth, we can figure out how far away they are. It’s similar to knowing that a car’s headlights have a certain brightness, and by observing how bright they look from a distance, you can calculate how far away the car is. When scientists use space telescopes like Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope to measure these objects, they find that the universe is expanding at approximately 70 to 76 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The second method takes a completely different approach. It uses the cosmic microwave background, which is essentially the leftover radiation from the Big Bang itself. Think of it as the oldest photograph of the universe we can take. This ancient light carries information about the universe’s composition and history. By analyzing tiny temperature fluctuations in this primordial radiation, scientists can work backward and calculate what the expansion rate must be today. When they do this, they get a different answer: approximately 67 to 68 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The difference might seem small to you—a gap of about 9 percent—but in science, this is huge. Both measurements are extremely precise, with error margins so small that they don’t overlap. This isn’t like two people estimating the height of a building within a few feet of each other. This is like one person saying the building is exactly 100 feet tall while another insists it’s exactly 109 feet tall, and both are absolutely certain about their measurements. The statistical likelihood of this being a coincidence is less than one in a million.

“The universe isn’t adding up—and it’s creating a crisis in cosmology,” as Nobel laureate Adam Riess has pointed out. And he would know. His team has been at the forefront of measuring the expansion rate using direct observations of supernovae.

So what does this mean? Let me break it down simply. Either our measurements are somehow wrong—perhaps our instruments have subtle biases we haven’t detected, or we’re misinterpreting what we’re seeing. Or, more dramatically, our fundamental understanding of the universe is flawed. The standard model of cosmology, called Lambda-CDM, is a remarkably successful theory that explains most of what we observe about the cosmos. But the Hubble Tension suggests it might be missing something crucial. There could be unknown properties of dark energy—the mysterious force accelerating the universe’s expansion. There could be new particles we haven’t discovered yet. Or there could be physics operating in the early universe that we don’t understand.

Have you ever had two different maps of the same territory that didn’t quite match up? That’s what cosmologists are experiencing right now. Our map of the early universe, derived from the cosmic microwave background, doesn’t align with our direct observations of the nearby universe. Something is off, and we need to figure out what.

One particularly intriguing possibility involves something called the “sound horizon.” In the early universe, sound waves traveled through the primordial plasma, creating patterns that we can observe today in both the cosmic microwave background and the large-scale structure of galaxies. The sound horizon—essentially the maximum distance a sound wave could have traveled before the universe became transparent—acts like a measuring stick for the universe. If the sound horizon was different than we think it was, it would affect all our calculations based on the cosmic microwave background. Recent research suggests that if something altered the sound horizon in the early universe, perhaps by changing how quickly the universe was cooling or by introducing new forms of energy, it could potentially resolve the tension.

Another explanation involves dark energy behaving differently than we expect. We currently think dark energy acts like a cosmological constant—a fixed property of space that never changes. But what if dark energy actually evolves over time? What if it was different in the early universe than it is today? This would be revolutionary because dark energy makes up about 68 percent of the universe’s total energy density. If we’re wrong about how it works, we’re wrong about something fundamental.

Then there’s the possibility of exotic new physics entirely. Some scientists have proposed undiscovered particles that could affect the universe’s expansion. Others have suggested that gravity itself might behave differently on cosmic scales than Einstein’s general relativity predicts. These ideas might sound wild, but remember—the evidence from multiple independent observations is forcing us to consider radical possibilities.

What makes this crisis particularly acute is that both measurement methods are gold-standard science. The cosmic microwave background measurements come from NASA’s WMAP probe and the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite, which took the most precise measurements ever of this ancient radiation. The direct expansion rate measurements come from multiple independent teams using some of the most advanced telescopes humanity has built. We’re not dealing with sloppy data or old-fashioned techniques here. We’re dealing with cutting-edge science that’s mysteriously contradicting itself.

“Perhaps the problem lies not in our instruments but in our models,” observes many researchers in this field. And that’s the real possibility that keeps cosmologists up at night. If our instruments and observations are correct, then something fundamental about how we understand the universe needs revision.

The implications of resolving this tension extend far beyond academic curiosity. The Hubble Constant determines the age of the universe. Using the expansion rate measured from supernovae, the universe is approximately 13.8 billion years old. Using the expansion rate calculated from the cosmic microwave background, it would be slightly younger. This affects our understanding of how stars and galaxies formed, when the first stars ignited, and what the universe’s ultimate fate will be. Will it expand forever? Will it eventually collapse? The answer depends partly on knowing the correct expansion rate.

Scientists worldwide are working on this problem from multiple angles. Some are improving the precision of supernovae measurements. Others are re-examining the cosmic microwave background data. Still others are proposing entirely new theories to explain the discrepancy. What’s remarkable is how this single measurement problem has become a catalyst for rethinking the foundations of cosmology.

The Hubble Tension reminds us that science is not a finished product. Our most sophisticated theories and measurements can still reveal unexpected contradictions. This is not a failure of science; it’s science working as it should. We observe reality, we test our understanding, and when we find inconsistencies, we investigate deeper. The universe is far more complex and subtle than we realized, and that complexity is what makes cosmology genuinely exciting today.