You might think ancient technology was all simple tools, dusty scrolls, and people arguing about philosophy under olive trees. But what if I told you that two thousand years ago, someone built a machine so complex, even today’s engineers scratch their heads when they look at it?

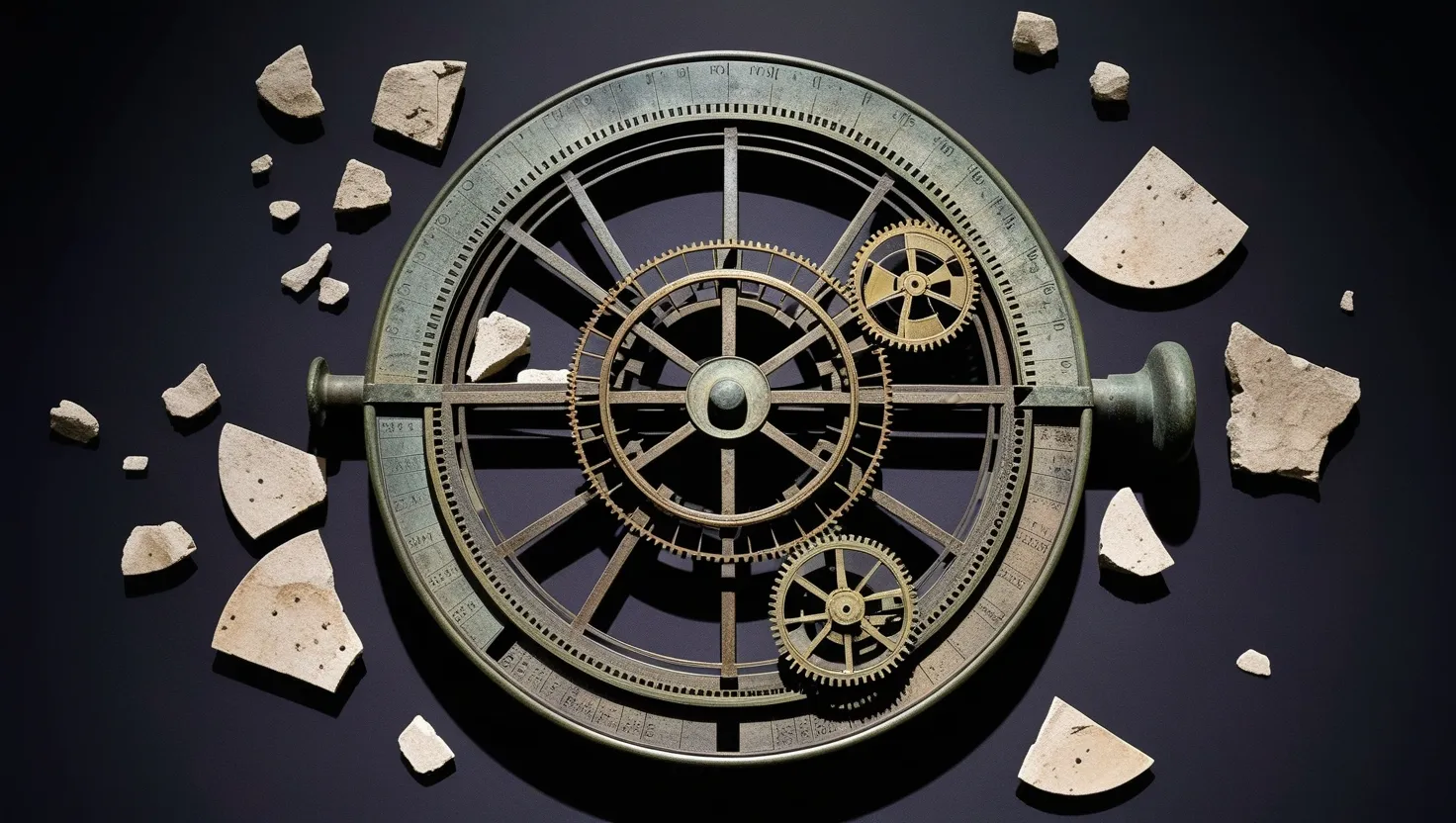

That’s the tale of the Antikythera Mechanism, a rusty lump from a forgotten shipwreck that gave us one of the greatest surprises in the history of science. It’s easy to overlook at first glance—shards of greenish bronze, fragments barely recognizable as anything but shipwreck junk. Yet, inside this battered box lies a story that keeps challenging what we thought we knew about the ancient world.

Imagine you’re deep underwater, off a Greek island. Sponge divers are collecting sponges (yes, real sponges), when one spots a statue arm sticking out from a pile of debris. Soon, the seabed’s covered with statues, coins, jewelry, and what looks like a corroded clock. This “clock” would later become famous: the Antikythera Mechanism.

The truth is, when I first read about it, it didn’t sound real. Ancient Greeks, building computers? Most of us barely made it through high school algebra, and here’s a device from 100 BCE with gears so small and delicate they wouldn’t be out of place in a watchmaker’s showcase.

Here’s where things get interesting. X-ray scans show the mechanism hid at least thirty gears, some with teeth so fine you need a microscope to see their details. The gears weren’t just spinning aimlessly—they were calibrated with precision to track the movements of the Sun, the Moon, and probably all five planets known to the Ancients. It could tell you the phase of the Moon, predict eclipses, and even point out when the next Olympic Games were coming up. To do this, you’d turn a little handle and the gears would whirl into life, moving pointers on the front dials—almost as if you had a physical calendar crossed with a star chart, right there in your hand.

“All truths are easy to understand once they are discovered; the point is to discover them.” — Galileo

What makes the Antikythera Mechanism so strange isn’t just what it did, but when it was made. For most of history, we assumed gear technology this complex only arrived in Medieval Europe, over a thousand years later. Differential gears—that’s the kind used in cars to distribute speed to wheels—shouldn’t have existed until the 14th century, according to conventional thinking. So, how did a Greek craftsman, with bronze instead of steel and hand tools instead of lathes, make a gadget with such mathematical precision?

Let’s be honest, it sounds a bit like finding a smartphone in an Egyptian tomb. Scholars have tried to place the device in its context. The best guess? It was built on the island of Rhodes, maybe by someone in the circle of Hipparchus or Posidonius, names mostly familiar to astronomy buffs. There are hints in old writings, like the Roman writer Cicero, who described similar machines supposedly designed by Archimedes. But, apart from those scattered references, nothing like the Antikythera Mechanism survived—no workshop tools, no other samples, and definitely no instruction manuals carved in marble.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” — Arthur C. Clarke

So what do we do when history hands us an object that doesn’t fit our tidy timelines? We argue. Some experts say this machine represents the peak of Hellenistic science, a one-off built for a wealthy patron or perhaps an educational model teaching astronomy. Others wonder if there once existed a whole tradition of such devices—lost in time because bronze was too valuable to leave lying around, or because knowledge got burned up in libraries or lost in wars.

Here’s a thought: could the Antikythera device be a survivor from a line of machines now vanished, leaving only rumors and broken artifacts behind? Or did one genius, now forgotten, pull off an engineering miracle that outpaced even their own era?

“It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.” — Eugène Ionesco

Think about how odd it is that this machine is alone. No one’s dug up a workshop filled with blanks and broken gears. No ancient engineer’s sketchbook has come to light. There’s just this single mechanism, as if someone took a snapshot of an entire science at its height and then swept everything else off the table.

Dig a little deeper, and the plot thickens. The Antikythera Mechanism wasn’t just about pure astronomy. It included cycles important to Greek religion, the prediction of festivals, and—disturbingly precise—the Saros and Metonic cycles that tracked lunar and solar eclipses. This blends the lines between what we’d call “science” and “belief.” Was it made for astrology? Was it to line up rituals with the heavens? Or did people use it to keep taxes and agricultural cycles in sync with the sky?

What is even stranger is how the mechanism seems to “know” about slightly tricky celestial motions. The Moon, for example, doesn’t travel in a perfect circle; its speed changes. The Antikythera Mechanism accounts for this using a clever pin-and-slot system—something you might expect from a watchmaker centuries later, not a Greek craftsman with a hammer and chisel.

If you’re starting to feel left out, don’t worry—you aren’t alone. Today’s watchmakers and engineers have tried to recreate the mechanism, and it’s still not clear how the ancient builder machined those teeth and made everything fit. It’s as if they had a blend of art, skill, and knowledge that has faded away.

Here’s a question to ponder: If a device like this could vanish from collective memory for centuries, what else might have disappeared without a trace?

Sometimes I wonder about all that lost knowledge. The Antikythera Mechanism survived only because its ship sank. Libraries in Alexandria and elsewhere burned, wiping out books and diagrams that might have told us who designed such things. Every time I see this crumbly set of gears, I imagine rooms lined with similar wonders—maybe even devices more advanced than this one, now gone forever.

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” — Thomas Edison

New technology, like high-resolution scans and X-rays, keeps uncovering more details. Scientists found faded Greek words engraved on the mechanism itself, almost like a user manual. Step by step, they’ve pieced the story together—not just how it worked, but how it was meant to be used. Each fresh reading leads to new ideas about what the device could do. In fact, with every discovery, more questions rear their heads.

For example, many earlier civilizations, like the Babylonians, kept excellent records of celestial events. It’s tempting to wonder: was the mechanism’s knowledge passed down in secret, or did the Greeks reinvent everything on their own? Maybe both happened. Or maybe, as some fringe thinkers propose, there was an even older lost civilization behind it all—but right now, evidence for that is thin.

“What we know is a drop; what we do not know is an ocean.” — Isaac Newton

Let’s stop for a second and imagine what life would be like if the Antikythera Mechanism hadn’t been lost. Would we have seen mechanical clocks or planet-tracking devices centuries before history says they appeared? Could the timeline of technology have been different? Sometimes, history is shaped more by what we forget than by what we remember.

Here’s another question: why wasn’t this kind of mechanical genius copied or improved upon? Did political changes, wars, or a shift in priorities pull attention away from mechanical inventions? Or did the knowledge die with a handful of people, leaving no one behind who could understand or repair such things?

Some feel strongly that the Antikythera Mechanism doesn’t rewrite history—it’s just a testament to how clever a few Greeks could be. But I think it’s a much larger reminder of how knowledge can slip away, leaving only myths or scraps for us to find later.

If we learned anything from the Antikythera Mechanism, it’s to be careful about drawing hard lines through history, saying this is the era of simple tools and that is the era of machines. Sometimes single artifacts like this one light up the darkness, showing that history is messier—and more surprising—than we’d like.

“Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.” — Carl Sagan

Next time you see a gear or a clock, think about that ancient box at the bottom of the sea, patiently waiting all those years. What would the person who made it think if they knew their creation would become famous after being forgotten? Would they smile, knowing they managed to speak to the future without ever writing a word?

Maybe the best idea is to stay curious. That means questioning what we think we know and being open to the idea that more mysteries, just as strange, are still waiting for us. Who knows? Maybe the next discovery is just under our noses—or buried in the deep sea, waiting for the right moment to resurface.