Deep Beneath the Baltic: A Mystery That Won’t Stay Silent

When Peter Lindberg and his team at Ocean X pointed their sonar equipment toward the seabed in June 2011, they had no idea they were about to spark one of the most talked-about underwater mysteries of our time. I’m going to walk you through this story step by step, because honestly, it’s far more complicated than the headlines suggest.

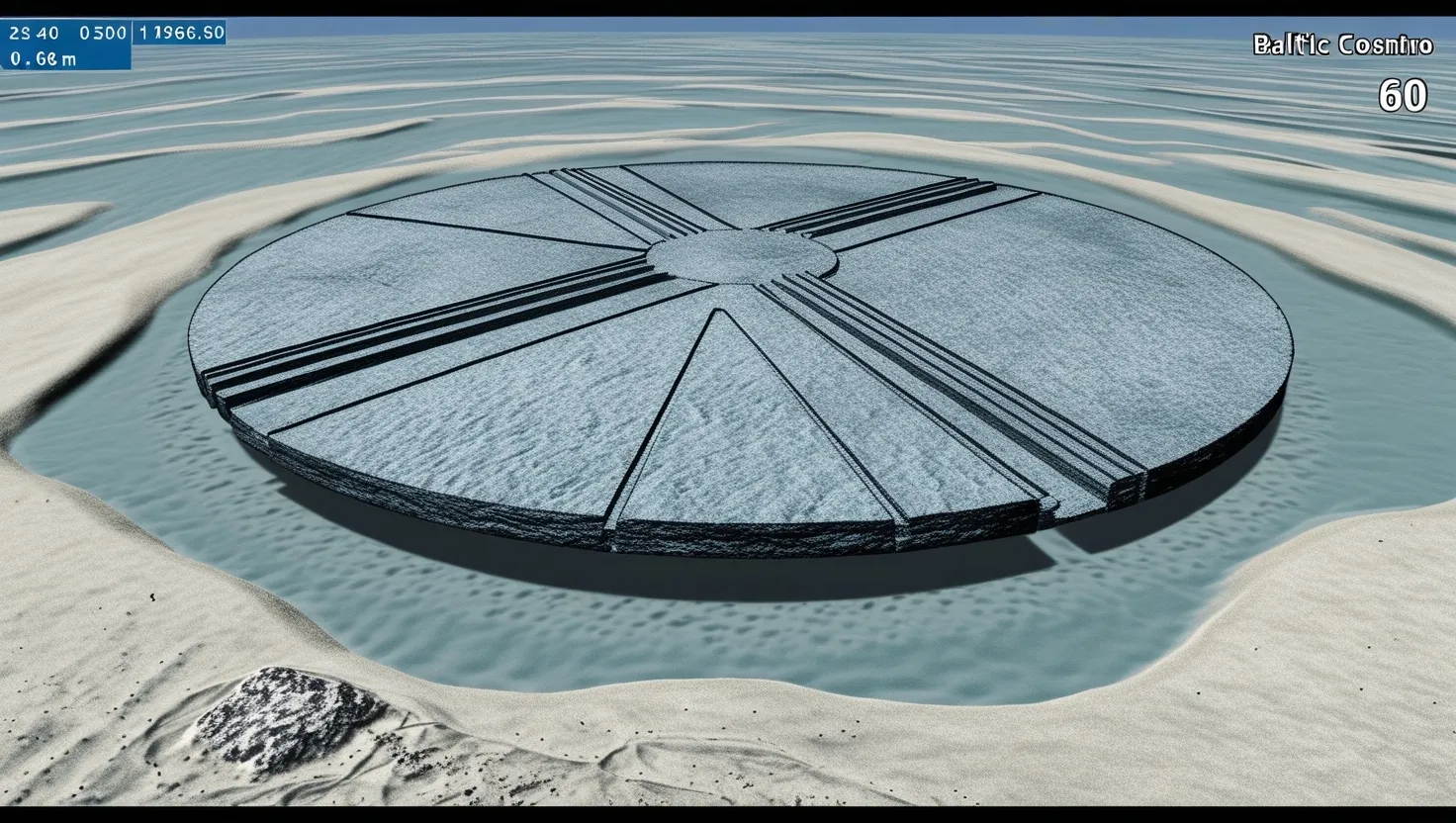

Picture this: you’re searching for shipwrecks in the Gulf of Bothnia, the northern part of the Baltic Sea between Sweden and Finland. Your sonar returns an image that makes your jaw drop. Instead of the expected scattered rocks or shipwreck debris, you see a massive circular structure about 60 meters across, sitting 90 meters below the surface. It looks almost designed, with what appears to be a flat top and strange formations extending from it. This is exactly what happened to the Ocean X team that summer day.

Now here’s where things get interesting. The object didn’t just look odd in the sonar images. The explorers claimed that when they got close to it, their electronic equipment started behaving strangely. Satellite phones went dead. Sonar instruments malfunctioned. Once they moved about 200 meters away from the structure, everything worked perfectly again. If I told you about this scenario in a science fiction movie, you’d probably think it was a setup for an alien contact story. But this was real, and it happened in our oceans.

The immediate response from tabloid newspapers was predictable: UFO. Sunken alien spacecraft. Lost city of Atlantis. The media ran wild with the story, and for good reason. The sonar images did look unusual. But before we get caught up in the excitement, let me tell you what actually makes this mystery worth discussing.

The object resembled something that caught everyone’s imagination, so much so that people compared it to the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars. It had a disc-like main body with what looked like a tail or runway extending from it for about 300 meters. The surface appeared to show cracks filled with a black substance nobody could immediately identify. There were also what seemed like construction lines and geometric patterns. For people seeing these images, the conclusion felt obvious: this had to be man-made. But by whom? And how long had it been down there?

Here’s what makes this genuinely puzzling. The Baltic Sea is geologically young, only about 8,000 years old. It’s not a region known for volcanic activity or seismic upheaval. This fact alone eliminates one major explanation that UFO enthusiasts might suggest. The sea floor simply doesn’t have the kind of geological drama that would create strange formations on its own through standard volcanic processes.

But here’s where the conversation gets really interesting. The region has experienced something far more powerful than volcanoes: ice ages. Imagine massive sheets of ice, some miles thick, advancing and retreating across the landscape over thousands of years. These glaciers were like cosmic bulldozers, carving up the earth, pushing rock and sediment around, and completely reshaping geography. When they finally melted around 10,000 years ago, they left behind a transformed landscape. This glacial history is the key to understanding almost everything about the Baltic region, including the seafloor where this mysterious object sits.

Swedish geologists Fredrik Klingberg and Martin Jakobsson examined samples from around the anomaly. Their analysis showed something that genuinely matters: the chemical composition matched naturally occurring nodules found in seabeds. The materials included limonite and goethite, both minerals that form through natural geological processes. Think of these like the building blocks of nature itself, not anything exotic or otherworldly. This suggested that what the explorers found might simply be an unusual but natural formation.

But I want to ask you something here: if this is just a natural formation, why does it look so perfectly circular? Why does it seem to have straight edges? Why the black material in the cracks? These questions aren’t silly. They’re the same ones that scientists have been asking.

Enter Jarmo Korteniemi, a Finnish planetary geomorphologist. His explanation was both simple and elegant. The object, he suggested, might be a drumlin. Drumlins are elongated hills formed by glacial action, typically aligned in the direction the glacier moved. They’re not rare, and they’re not mysterious once you know what to look for. Korteniemi pointed out that similar mounds exist throughout the Bothnian Sea, all aligned in the same direction. The “runway” everyone found so suspicious? Probably just part of a larger group of these natural formations, he said.

Yet here’s where the story refuses to become ordinary. Andreas Olsson, an underwater archaeologist, looked at the same object and came to a completely different conclusion. He believed the object appeared cut or molded, suggesting human construction. His position wasn’t based on speculation alone. In 2024, archaeologists discovered Europe’s oldest man-made megastructure in the nearby Bay of Mecklenburg. This was a kilometer-long wall made of 1,500 granite stones, built approximately 11,000 years ago by Palaeolithic communities. The structure sat at a depth of 21 meters. This discovery proved that ancient people were capable of creating enormous underwater structures. So why couldn’t the Baltic Sea anomaly be something similar?

Here’s a detail that intrigues me personally. The Ocean X team had found legitimate treasures before. They discovered a Swedish steamer off the Åland Islands containing over 1,000 bottles of cognac from 1917. They found three other wrecks from the Russian Revolution era, salvaging thousands of bottles of champagne along with three Fabergé eggs worth about 84 million dollars combined. These weren’t amateurs making wild claims. These were experienced professionals with a track record. Would they risk their reputation on something they didn’t genuinely believe deserved investigation?

The electrical interference theory, though, is where things get murky. Some claimed that the object must be made of metal to cause such disruptions. But here’s the thing: not every conductive material is metal. Rock formations can sometimes produce electromagnetic effects under the right conditions. Mineral compositions in certain geological formations can interfere with electronic equipment. So the malfunctioning phones and sonar don’t necessarily prove anything extraordinary.

There’s also another angle worth considering. Peter Lindberg mentioned that his team took precautions like turning off cell phones and GPS before the expedition. They wanted to avoid being tracked. Yet a Swedish military vessel appeared while they worked, according to their account. Why would the military show interest in a salvage operation in international waters? Was there genuine concern about the discovery, or was this merely coincidence and heightened suspicion?

Let me pose this question to you: what would convince you that something is genuinely mysterious versus simply unusual? Would it be visual evidence? Physical samples? Lack of conventional explanation? The Baltic Sea anomaly sits in this uncomfortable space where none of these criteria are completely satisfied.

The truth is, most experts now believe the object is a natural geological formation shaped by glacial processes. The consensus leans heavily toward this explanation. But “most experts” is not the same as “all evidence.” Some questions remain unanswered. Some details don’t fit neatly into the glacial deposit theory. The explorers’ accounts of equipment malfunction never received satisfactory explanation. The perfectly circular shape and geometric patterns still catch the eye.

As the famous oceanographer Jacques Cousteau once said, “The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever.” The Baltic Sea anomaly demonstrates exactly this sentiment. The ocean keeps secrets, and sometimes those secrets look stranger than our imaginations can process.

What I find most valuable about this mystery isn’t necessarily discovering what the object “really is.” It’s the reminder that our planet still has places we don’t fully understand. It’s the recognition that exploration matters, that asking questions matters, and that sometimes the most important discoveries aren’t about finding aliens or lost cities. They’re about learning how our world actually works beneath the surface we live on.

The Baltic Sea anomaly will likely remain a topic of discussion and debate. New expeditions could yield fresh data. New geological research might provide clearer answers. Or it might simply remain one of those interesting oddities that reminds us how much we still have to learn about Earth itself. And honestly, there’s something valuable in that uncertainty. It keeps us curious. It keeps us asking questions. It keeps us looking deeper.