If I could hand you one book guaranteed to spark a thousand questions, it would be the Voynich Manuscript. This strange artifact, dating from the early 1400s, sits in a library vault, tempting researchers and puzzling codebreakers. It’s a small volume, about the size of a large paperback, but the mysteries inside have consumed the minds of cryptologists, linguists, botanists, and even physicists. What keeps the buzz alive, despite centuries of scrutiny? Let’s wander through the thickets of its legends and facts together and see if we end up with more answers—or more questions.

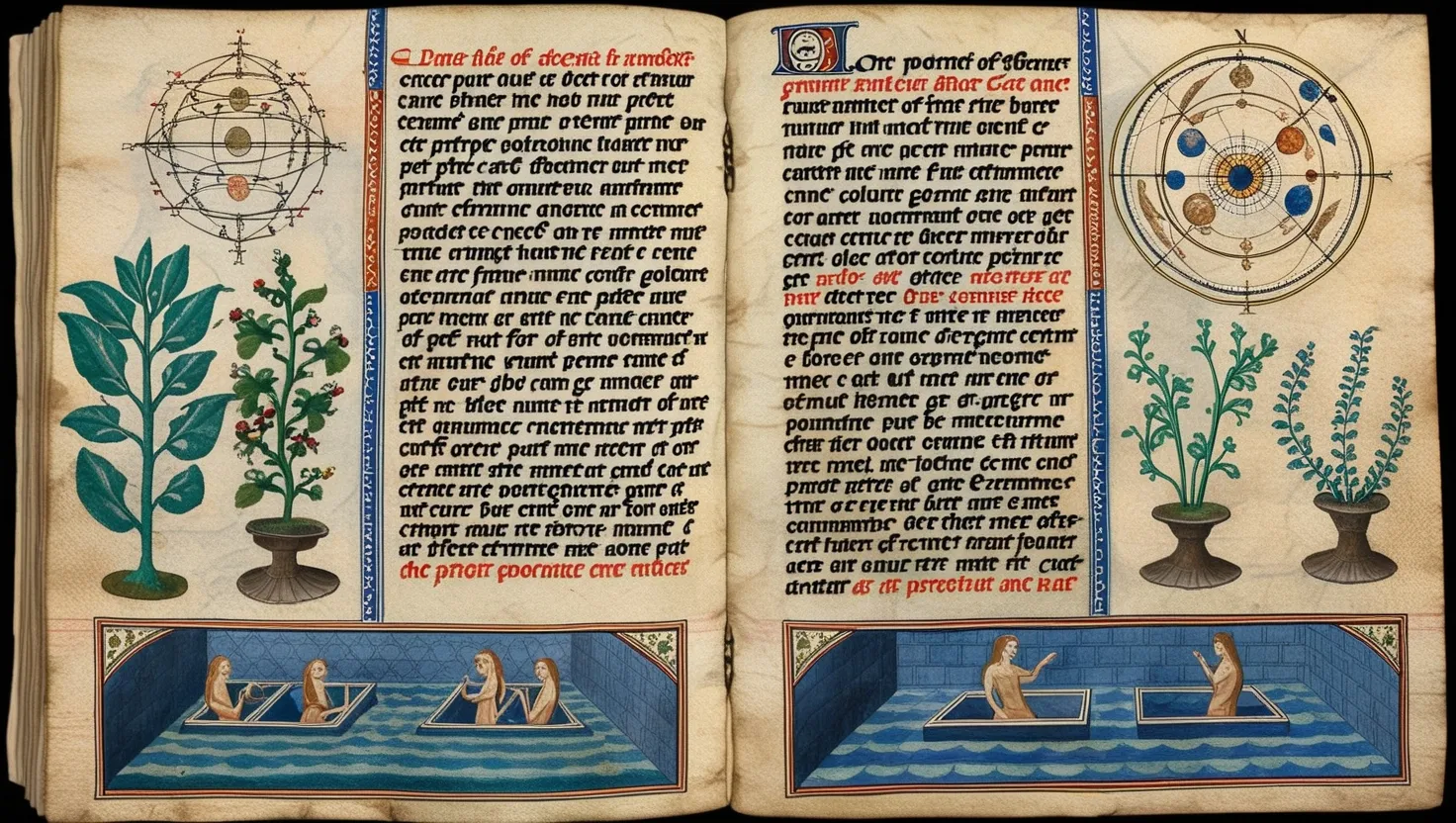

First encounters with the Voynich Manuscript are a sensory overload. Its pages are filled with dense, looping script in a language no human can read. Even stranger are the illustrations: plants that never existed, naked women bathing in pools shaped like abstract plumbing systems, and astronomical charts with suns and moons that defy any clear categorization. I always find myself asking: if someone wanted to create a puzzle, why not just use a code we could eventually beat? And if this is all nonsense, why invest so much effort in creating such detailed art?

Let’s back up to its confirmed origins. Radiocarbon tests place the parchment’s creation in the early 15th century. That means we’re not dealing with a modern fake—unless someone in our century was clever enough to hunt down and reuse blank medieval parchment, which experts agree would be an absurdly costly and unnecessary move. The ink, too, matches what medieval scribes used. Whatever the Voynich Manuscript is, it is old. The real puzzle is what happened next.

How did it travel through history so quietly? Its earliest traceable owner, based on faded inscriptions, links it to a Central European physician connected to the court of Emperor Rudolf II. But after a few gaps and jumps, the book’s trail goes cold until Wilfrid Voynich, a rare book dealer, bought it in Italy in 1912. Imagine the excitement: peeling back the pages of an untouched, undecipherable manuscript, hoping it might reveal the lost language of a forgotten civilization—or perhaps even a secret code that could change our understanding of medieval science.

The heart of the matter: what is written in those pages? Many have pored over the script, convinced it’s a code, perhaps masking lost wisdom or scientific secrets. Hundreds of cryptographers have tried, including some who cracked wartime codes. They all failed. Some argued it might be written in shorthand Latin or an obscure dialect; others have tried Asian, Semitic, and even constructed languages. High-powered computers searched for repeating patterns, matching word clusters to pictures and counting character frequencies. Some found hints of structure—maybe like a real language, maybe not. No translation has ever emerged.

A handful of researchers have gone further. They examined the manuscript’s statistical structure and found it doesn’t quite match natural languages but also doesn’t fully resemble random gibberish. Some sections seem to have topic clusters: new “words” appear with new types of illustrations, and repeats pop up in similar places. But can structure alone prove meaning? That’s up for debate, and it’s a lively debate.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once said, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Yet, in Voynich land, silence is hardly the point. Instead, nearly everyone has a theory. The most popular (and controversial) is that it’s all a hoax—designed either for profit or as an elaborate prank on a Renaissance scholar. This theory appeals to skeptics: the script doesn’t translate, the plants can’t be found anywhere, and the stars don’t match up. Was someone trying to trick a rich or powerful patron out of their money? Or perhaps testing the intellectual vanity of codebreakers and scholars?

If you find it hard to believe someone would go through all this trouble for a joke or a swindle, you’re not alone. The manuscript’s text is regular, complex, and lengthy—far more than most known forgeries or codified tricks of the era. Some experts argue a hoaxer would never bother with so much consistency across 200+ pages. Long, coherent writing like this requires significant knowledge, time, and effort. If meaning exists, it’s buried so deeply no one has found it; if it’s a fake, it’s a masterpiece.

On the flip side, what if the manuscript is not a hoax but an honest attempt to encode lost knowledge? Some speculate it’s a record from a forgotten language or a lost scientific culture. Could it be the remnants of an extinct script, passed down by a vanished sect? Or perhaps secret notes in a code invented for personal study—think of a scholar fearful of persecution, hiding her findings from prying eyes.

If I could ask you—what makes you believe? Is it the ancient parchment? The strange diagrams? Maybe the manuscript’s real significance is less about its content and more about what it represents: the possibility that something utterly alien could pass through history without anyone ever knowing its source.

And then there’s the most out-there theory of all: the manuscript came from somewhere beyond this world. Some propose it records the knowledge of visitors not born on Earth, pointing to the non-human botanical forms and astronomical oddities. This idea, let’s be honest, holds more appeal for science fiction than for serious scholarship. Still, isn’t it fascinating that a medieval book can still provoke modern ideas about life elsewhere in the universe?

Arthur C. Clarke famously said, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” What happens when we confront knowledge that looks indistinguishable from nonsense—or from the works of an entirely different civilization? The Voynich Manuscript sits at this crossroads.

One little-discussed facet is the manuscript’s effect on modern science and linguistics. Recent years have seen artificial intelligence put to work, hoping that pattern recognition will do what human eyes could not. Algorithms cluster “words” and link illustrations, offering new hints but still no answers. I find myself wondering: will a computer ever crack the code, or is the secret simply not there?

Meanwhile, botanists, astronomers, and historians keep searching for clues in the pictures. Some think a few plants resemble New World specimens, suggesting secret early contact between continents. Others believe the images are deliberately misleading, drawn to frustrate would-be codebreakers.

Is the Voynich Manuscript a mirror showing us our limits? Or, as some hope, is it a doorway: a reminder that knowledge itself can be hidden in plain sight, waiting for minds yet to come? How would you approach it if you had a month with the manuscript and unlimited resources—where would you begin?

Albert Einstein reminds us, “The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.” Scholars continue to tackle the Voynich Manuscript not only because of what it might contain but because it challenges our sense of what is possible. How do you classify something when you have no frame of reference?

As experiments continue, new theories pop up every year. Some believe the images are allegorical, not scientific; others think the book’s creators were creating an art object—meant to be beautiful but incomprehensible. Some think we’re missing a key: an original code book, a clever cipher, or perhaps just a lost translation method.

Ultimately, I am left with more wonder than certainty. The Voynich Manuscript is more than a puzzle—it’s a symbol of how much remains beyond our grasp. The strange writing dares us to think beyond simple answers. The odd plants invite us to question nature and knowledge. The uncertain history challenges us to see how little we truly know about the past.

“What we know is a drop, what we don’t know is an ocean.” Isaac Newton’s words echo as we consider the Voynich Manuscript. Whether code or hoax, alien or medieval art project, its greatest value may be what it reveals about our hunger to seek, create, and imagine. If there comes a day the manuscript is suddenly read like any other book, perhaps what we’ll lose is not just a mystery, but a challenge that has united thinkers across centuries.

Before you go, let me ask: will the Voynich Manuscript ever give up its secrets, or is its real purpose to remind us that not every question has an answer?