The Shroud of Turin is one of those things that refuses to sit quietly in a museum box. It is just a long piece of old linen with a faint image of a man on it, yet it has started fights between bishops, split scientists into camps, and pushed believers and skeptics to ask questions they normally avoid. Is this really the burial cloth of Jesus, or is it a brilliant fake from the Middle Ages? And more importantly, why does this question bother us so much?

Let me walk you through it in simple words. Imagine I am explaining this to a friend who hates big words and long lectures. That friend is you. I will keep us away from fancy language and stick to clear, direct talk.

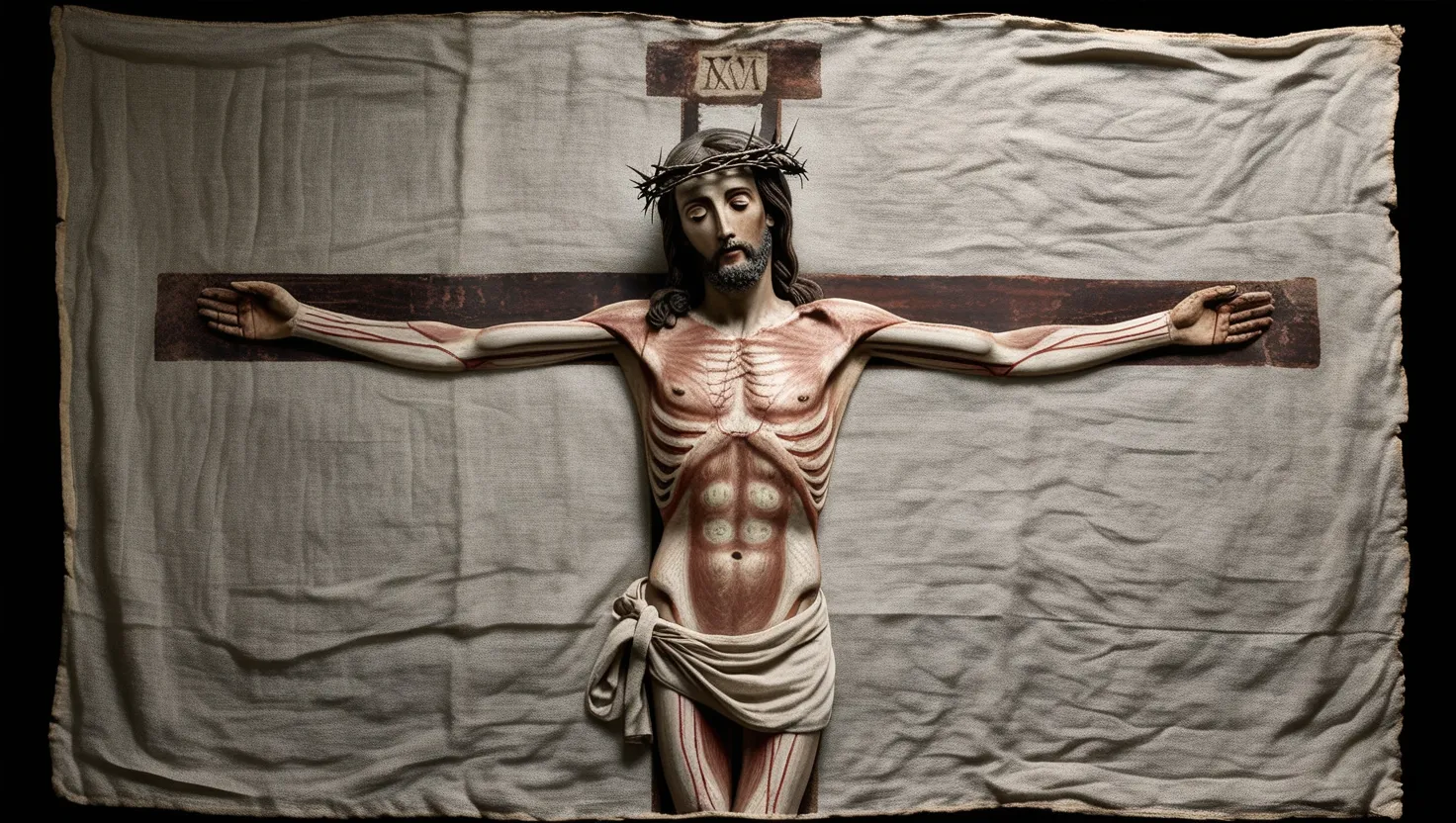

The Shroud is a rectangular linen cloth, a little over four meters long, with a faint front-and-back image of a man who looks like he was beaten, whipped, and crucified. The wounds on the image match what the New Testament describes about Jesus: bloody head wounds like from a crown of thorns, scourge marks on the back, pierced wrists and feet, and a large wound in the side. That is enough to make many people say, “This must be Jesus.” Others say, “Or it must be someone who wanted you to think it is Jesus.”

One of the strangest things about the Shroud is the way the image sits on the cloth. When experts look at it under a microscope, they find that the color only affects the very top surface of the fibers. It is like a sun-tan that touched only the outer skin of the threads, not paint soaked in. No brush strokes, no pigment layers like normal art, no clear sign of any paint binder. If it is a painting, it is an extremely odd one. So right away we are in a weird space: it looks like art, but it does not behave like normal art.

Here is where it gets more curious. In 1898, when an Italian photographer took the first photo of the Shroud, he made a shocking discovery in the darkroom. On his negative plate, the image popped out like a positive photograph. The cloth itself acts as if it is already a photographic negative, long before photography was invented. If you look at the Shroud with your eyes, the image is pale and ghostly. Reverse it like a photo negative, and the face suddenly comes to life with depth and contrast. How could a medieval artist create something that only makes full visual sense once photography exists, centuries later?

On top of that, modern image analysis shows that the intensity of the image on the Shroud carries three-dimensional information. When the brightness of the image is fed into special computer programs, it creates a reasonable 3D model of a human body. Regular paintings do not do this. If you run a photo or a painting through the same process, you get strange distortions, not a realistic 3D relief. So we have a cloth that behaves like a faint photographic negative with built-in 3D data. That is not what you expect to find in a medieval church treasury.

But then comes the famous scientific blow: radiocarbon dating. In 1988, three laboratories tested tiny pieces of the cloth using carbon-14 dating. Their results placed the cloth between 1260 and 1390 AD. That sounds as if the Shroud is clearly medieval, about the same time it first shows up clearly in European records. To many skeptics, that was the end of the story. Why argue further? The date says “Middle Ages,” so case closed.

If it were that simple, we would not still be talking about it today.

Some scientists and researchers argue that the samples tested in 1988 were taken from a corner of the cloth that had been repaired after a fire in 1532. That fire partly burned and scorched the Shroud, and nuns supposedly rewove some damaged areas. If the test took fibers from an area with mixed original linen and newer threads, then the date might be too young. Others point out that centuries of smoke, handling, oils from hands, fungi, and bacteria could change the carbon content enough to confuse the dating.

Are these arguments perfect? No. But they are not just “because we want it to be older.” They point to real problems: little sample area, possible repair threads, and complex contamination. More recent technical studies of the corner area show odd weaving patterns and chemical differences compared to the rest of the cloth, which support the idea that the 1988 sample might not be fully representative of the original fabric.

So we are left with a puzzle. The radiocarbon test says medieval. The image features do not fit easily with known medieval techniques. How do we hold those together in our minds without rushing to one side?

Let’s also talk about the blood. Many investigators say the reddish stains on the cloth test as real human blood, even with indicators of blood breakdown and a rare AB blood type. The flow patterns match what you would expect from someone hanging on a cross: gravity pulls blood down the arms, pools near wounds, and streaks in realistic ways. If a medieval artist did this, they did not just smear red paint. They seem to have carefully followed actual injury patterns.

One small but important detail: the nail wounds in the image are not in the palms but in the wrists. In many old paintings, Jesus is shown nailed through the palms, which is anatomically weak for holding a body on a cross. Modern medical and forensic studies show that nails placed closer to the wrist can support a person’s weight much better. How many medieval artists knew that? Most artworks of the time did not. Yet the figure on the Shroud matches modern forensic expectations.

This leads to an awkward question: if a forger did this, did they understand details that medical science would only clarify many centuries later? Or are we reading too much into the image with modern eyes and tools?

Now let’s shift from science to history. We can track the Shroud clearly in Europe back to the mid-1300s, when it appears in Lirey, France, owned by a knight named Geoffrey de Charny. Soon after its public showings begin, the local bishop protests. In a famous letter, he calls it a fake and claims that the artist confessed. That sounds like a solid blow against authenticity. Yet no confession text survives, no name is given, and we only have the bishop’s words from years after the events. It might be true. It might be politics. Relics brought in money and prestige, and church politics in that era were messy.

After that, the Shroud passes to the powerful House of Savoy, becomes a dynastic treasure, is carried from city to city, saved from fires and wars, and eventually ends up in Turin, where it still is. At one point it is even partly burned, with patches carefully sewn on. All this movement means more handling, more exposure, more chances for contamination—again, important when we think about dating and material tests.

But what about before France in the 1300s? This is where things get hazy and full of theories. Some historians and writers argue that the Shroud is the same as the “Image of Edessa” or “Mandylion,” an ancient cloth with an image of Jesus’ face, once famous in the Eastern Christian world. They say that if you fold the Shroud in a certain way, you get just the facial area, which might match those older descriptions. There are texts that talk about a holy image of Christ not made by human hands, hidden and revered in the East, possibly later brought to Constantinople. Records from the 1200s even mention a cloth with an image of a crucified man in Constantinople, before it was looted during the Crusades. After the city falls and is plundered, this object disappears. Some say that is when the cloth begins a secret journey west that ends in France.

Is this proven? No. Is it possible? Yes. Ancient and medieval sources are often vague and biased, and many objects changed names and stories over time. But it shows that the Shroud fits into a wider stream of traditions about sacred images of Christ that predate the 1300s.

So where does that leave us? We have strong arguments both ways, and neither side can absolutely crush the other. That is unusual. Many relics are clearly fake once you look closely. This one resists easy dismissal and easy belief.

Let me ask you something: what would change for you, personally, if the Shroud were proven real beyond doubt? Would you live differently? Would you treat people differently? And if it were proven fake, would your deeper questions about life, suffering, and hope disappear? For most honest people, the answer is no. The Shroud does not create faith from nothing, and it does not destroy it either. It mostly reflects what people already lean toward.

Here is something we often skip: even if the Shroud is medieval, it might still be an amazing work of art and theology. To design a cloth that captures both suffering and peace, that uses absence of strong color to create presence of emotion, that somehow encodes a kind of three-dimensional “memory” of a body—this would be one of the most brilliant pieces of devotional art ever made. Instead of thinking “fake, therefore worthless,” we might ask, “What kind of believer would spend that much care to create such a powerful symbol of the Passion?”

On the other hand, if it is genuinely from the first century and truly connected to Jesus, then it is not just a relic; it is also one of the most personal historical traces of a specific human life in antiquity. It would bridge the gap between text and flesh in a way no book can. For many, that is why it feels so charged: it is not abstract. It is an image of a body that has been hurt.

I want you to also notice how the Shroud exposes the limits of our tools. Carbon dating is excellent, but not magic. Image analysis is clever, but can be over-interpreted. Historical documents are valuable, but often incomplete and biased. The Shroud sits at the intersection of all three: science, history, and faith. None of these fields can fully own it. Whenever one tries to shout the others down, it looks weaker, not stronger.

So maybe the more honest way to treat the Shroud is not as a weapon in a debate, but as a mirror. When people look at it, they do not just see a man on a cloth; they see their own attitude toward mystery, proof, doubt, and hope. Do you demand absolute proof before you trust anything? Do you dismiss what you cannot fully explain? Do you rush to believe what comforts you? The Shroud quietly pushes us to test these habits.

There is also a quieter question that the Shroud raises: why do we care so much about physical traces of holy people? Why are we drawn to bones, cloths, drops of blood, bits of wood from supposed crosses? Maybe it is because we are physical creatures ourselves. We do not just think; we touch, we see, we smell. A story on a page is one thing. A piece of cloth that might have wrapped a tortured body is another. It makes pain and hope feel more solid.

But that is also where we can get lost. If we depend on objects to support our beliefs, we become fragile. If a relic falls, our faith falls with it. The healthier stance is to see something like the Shroud as a sign, not a foundation. It can move us, challenge us, comfort us, but it should not replace the harder work of living well, loving others, and facing our own faults.

You might be thinking, “So what do you think? Is it real or fake?” That is a fair question. The honest answer is: we do not know for sure yet, and we may never know. The physical tests and historical research keep moving, and occasionally new data appears that complicates both sides. Anyone who claims it is “obviously fake” or “obviously genuine” is skipping over real difficulties.

Maybe a better question is: “What can I learn from how people react to it?” You see scientists forced to admit the limits of their methods. You see believers forced to ask if their trust depends too much on objects. You see historians juggling patchy records. You see artists and image experts confronted with something that should be easy to copy if it is simple art, yet remains stubbornly strange.

If you ever get to stand in front of the Shroud, you might be surprised by how faint it is. It is not bright, not dramatic like a painting. It almost hides from you. You have to lean in, let your eyes adjust, and slowly the face comes forward. Maybe that is the quiet lesson it offers, whether it is a divine imprint or a medieval masterpiece: truths that matter most to us are often not loud and obvious. They ask us to slow down, to pay attention, to admit what we do not know, and to decide what we will do with the questions that remain.

So I will leave you with one more simple question: even if the Shroud never gives us a final answer about itself, what if its real value is the way it keeps pushing us to ask better questions about ourselves?