What draws me so deeply into the story of the Shroud of Turin isn’t just the faded imprint of a suffering man or the centuries of prayers whispered over its linen surface. It’s the patchwork of science, myth, and genuine wonder that gathers like dust around this mysterious relic. I find myself returning again and again to two questions: What is the Shroud? And why do people care so much about it, even now?

“Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.” – Albert Einstein.

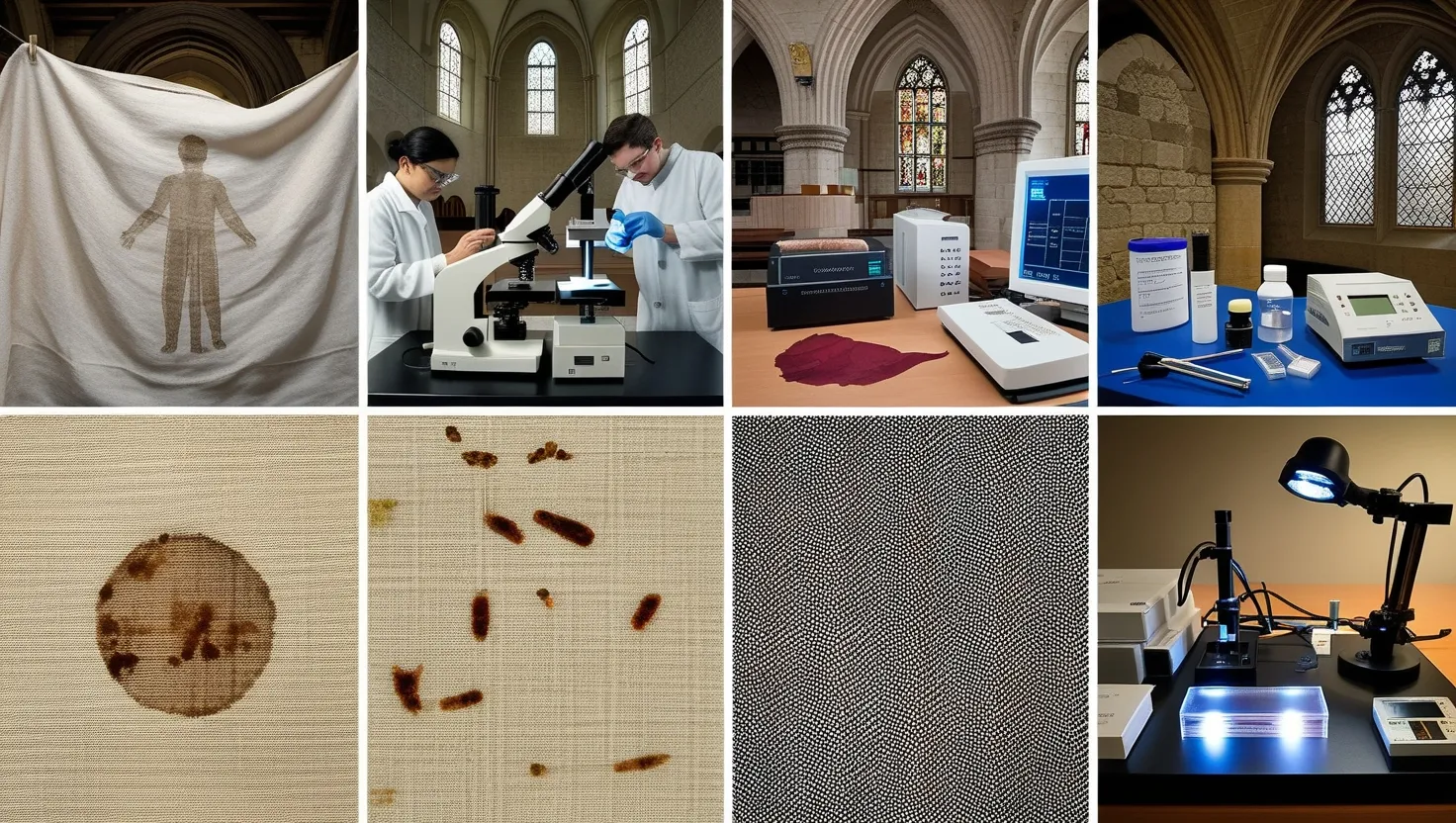

The Shroud’s fame exploded when it was photographed in 1898. The result was unsettling: under the lights of a camera, the faint image became a negative, revealing clear facial details and anatomical features that hadn’t been visible to the naked eye. Suddenly, it wasn’t just a piece of ancient linen—it was something else, with properties that seemed awkwardly ahead of its time. Why would a medieval forger create an image that only makes sense as a photographic negative, long before photography existed?

I often think about the people who have handled the Shroud over centuries. Picture the medieval knights in France, displaying it at public ceremonies, or the cautious church officials restoring sections after a fire. Each left a fingerprint in the fabric’s historical puzzle. Yet traces of pollen on the linen point toward regions that include Jerusalem and the Middle East, fueling the theory that this cloth might have traveled the same roads trodden by pilgrims and traders over a thousand years ago. How do these bits of botanic evidence fit together with what we know about ancient Mediterranean trade? Is it possible the Shroud made its way across continents, carried in secret, protected by believers desperate to preserve their treasure?

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.” – Albert Einstein.

When scientists get their hands on the Shroud, the conversation shifts from legend to lab. The 1978 research project, fueled by the efforts of American and European experts, examined every fiber they could. They discovered that the image isn’t painted, dyed, or stained—it isn’t even scorched by fire, despite surviving at least one catastrophic blaze. Instead, the image rests only on the very top threads, less than a hair’s breadth thick. No known painting technique matches this effect.

How could such a delicate imprint form? Some theorists now suggest it may have resulted from a flash of energy—light so powerful that it could bleach the linen’s surface while preserving the underlying material. This isn’t just science fiction; researchers have tried to simulate the effect with ultraviolet radiation blasts, albeit on modern cloth, and found some similarities. But no one has managed a perfect replica. I ask myself: If an artist set out to mimic this technique with the tools of the 1300s, could they have come close? Could chance or accident create such an effect—or is something more remarkable at work?

“It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.” – Eugene Ionesco.

There’s more than just a shadowy figure waiting behind the Shroud’s mysteries. The blood stains mark wounds that fit the biblical crucifixion narrative—a puncture in the side, traces of a crown of thorns, lines down the back like lash marks. Modern forensic tests indicate it’s human blood, and more specifically, type AB, which is rare but known in communities from the Middle East. Intriguingly, these blood marks were laid down before the shadowy image appeared, a detail that fights against the idea of a medieval forgery. Why would a trickster bother with this sequence? And how could they have done so unknowingly in a way that would only later be detected by blood analysis unavailable for centuries?

“If you want to find the secrets of the universe, think in terms of energy, frequency and vibration.” – Nikola Tesla.

The dating of the Shroud tests my patience, and perhaps yours as well. In 1988, three laboratories used radiocarbon dating and placed it firmly in the medieval period, between 1260 and 1390. Headlines declared it a clever fake. Critics immediately found fault with the samples—were they taken from an area patched after the Chambery fire in 1532, skewing results? Later analysis argued contamination by bacteria and restoration efforts could have muddled the carbon clock. More recent textile analysis and tests like vanillin degradation, which measures the chemical aging of linen, offer much older dates. Each scientific breakthrough leads to more questions than answers.

So how do we bridge the distance between faith and science? For some, the Shroud is the genuine burial cloth of Jesus: a physical touchstone of resurrection and redemption. For others, it’s history’s longest-running hoax, perhaps manufactured to feed medieval piety or fuel church coffers. A surprising number of scientists—studying pollen grains, the type of weave, and the image formation—not only avoid taking sides but even seem thrilled by the ambiguity itself.

“What we know is a drop, what we don’t know is an ocean.” – Isaac Newton.

I catch myself wondering about the artisans who wove that original linen. The herringbone pattern isn’t common for European medieval textiles, but it fits with techniques used in the Middle East during the 1st century. What inspired them to pick that design? Was the fabric intended for someone important, or was it a humble piece that gained mythic stature by chance?

Some researchers even use digital modeling to challenge the Shroud’s authenticity, arguing that it matches the contours of a sculpture better than it fits a true corpse. Could the image have been produced using heated statues or chemical reactions more familiar to early alchemists than to modern scientists? Why would someone go to such lengths—and would they have had the means? Would I?

“I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.” – Albert Einstein.

As I work my way through academic papers, old monographs, and recent debates, what stands out isn’t just the ongoing feud between believers and skeptics—it’s the way the Shroud continues to change the conversation. New testing methods arrive, challenging older results. Digital overlays sharpen, obscure, and re-contextualize facial details. Religious authorities debate whether to protect the relic or open it to new forms of analysis. Every generation finds a new question, a fresh angle, some point of friction that keeps the Shroud relevant.

Have you considered what it means to have unanswered questions at the heart of both our science and our faith? The Shroud reminds us that some mysteries aren’t solved—they’re studied, cherished, and argued about.

“A wise man can learn more from a foolish question than a fool can from a wise answer.” – Bruce Lee.

For now, the linen artifact remains in Turin, tended by cautious hands and secured behind glass, its image both inspiration and provocation. I suspect that, centuries from now, new viewers will stand before it, asking the same old questions dressed in the language of their time. Whether the Shroud tells the story of a man transformed by suffering, the intricate workings of medieval craft, or the quirky unpredictability of material science, it offers us something vital: a puzzle not yet finished.

So, I return to my questions: What is the Shroud, and why do people care? In the end, maybe it’s the questions themselves that make the Shroud matter. Would you agree?